This Supreme Court decision overturned limits set up by Congress for spending by corporations on federal elections. As a result, corporations can pour even more money into influencing the outcome of elections. Unless Citizens United is overturned, candidates who have criticisms of corporate environmental or social behavior will have an even harder time matching the spending of those who subordinate the real interests of their constituents to the best interests of the corporations. And pressure will increase even further for candidates to appeal for money from those who have it—the richest people in the society—and that will increase the degree to which those with money will shape the policies of those candidates.

In order to reach its decision, the Supreme Court had to affirm previous interpretations that corporations are “persons” under the Fourteenth Amendment (although history makes clear that the intent of the framers of that amendment was to ensure that African Americans would not be denied their due process of law as they were at the time, and that when they used the word “persons” they meant what most people mean, not an inanimate legal fiction called “a corporation”).

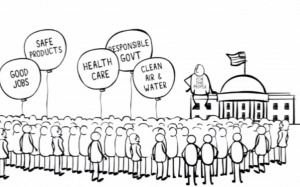

The Supreme Court has a solid conservative or right-wing majority and has shown frequently in the past decade that it will use its power to overturn significant constraints on corporate power. The only way we ordinary folk have to change this is to pressure our congressional representatives and members of our state legislatures to adopt a constitutional amendment that would explicitly overturn the reasoning behind Citizens United. So far, most congressional representatives, including those in the Democratic majority, seem timid about daring to move for a constitutional amendment. Instead, they have been considering lukewarm proposals that won’t actually challenge the right of corporations to spend unlimited funds to influence the outcome of elections. So we have to be the ones to fight for an amendment that rejects the idea of “corporate personhood” and equating money with speech.

If all that happens is that Citizens United is overturned, then we go back to the status quo ante, namely the way it was before the 2010 Supreme Court decision. But the truth is that corporate dominance was pretty powerful even before that, and most candidates had to spend an inordinate amount of their time in public office seeking the favor of the wealthy to get donations from them.

Getting a constitutional amendment passed will take a huge amount of work over the course of many, many years. The first method is for a bill to pass both the House of Representatives and the United States Senate, by a two-thirds majority in each. Once the bill has passed both houses, it goes on to the states. This is the route taken by all current amendments. Because of some long outstanding amendments, such as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, Congress will normally put a time limit (typically seven years) for the bill to be approved as an amendment (for example, see the Twenty-First and Twenty-Second). It must then be approved by three-fourths of all the states.

The second method prescribed is for a constitutional convention to be called by two-thirds of the legislatures of the states, and for that convention to propose one or more amendments. These amendments are then sent to the states to be approved by three-fourths of the legislatures or conventions. This route has never been taken, and there is discussion in political science circles about just how such a convention would be convened and what kind of changes it would bring about. We do not embrace this second direction, in part because we fear that many extraneous issues would be raised and the tinkering might produce a worse result than leaving things as they are now. The first method, on the other hand, has the advantage that we know what we are getting and at each stage can use the democratic process to support or oppose it.

Now here comes the main point:

If we are going to spend this kind of time and energy for years and years, then we ought to do so on an amendment that, if passed, would dramatically improve our democratic process as well as our ability to protect the domestic and global environment. Then, at least, the effort would be worth it.

Yes, that is more likely, though it would be very unlikely in the foreseeable future for such an amendment to receive the two-thirds vote it would need in both houses of the Congress.

What we have to face is that the process of building support for any such amendment is going to take many years of political work through every possible corner of America’s civil society—its civic organizations, its schools and universities, its churches and synagogues and mosques and ashrams, its professional organizations and unions, its media, and its neighborhood organizations.

We believe that if we are doing all this work, it should be done with the following goal: even if we fail to ever get the amendment passed, we will succeed in developing a new public awareness of what a more democratic politics and environmentally responsible economy might look like.

Moreover, this process is not merely educational. In the years that women and their allies sought (and failed) to get the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) passed by the states, they managed through their campaign to convince many people of the need for a fundamental change in the way women were treated. Many of those changes eventually were adopted by state and city governments, corporations, the media, and many individual citizens. There were even some who adopted some of the program of the ERA in order to prevent the ERA from getting passed into law—they could say, “We already have practices that correspond to what you are seeking, so we don’t need an amendment.” That same thing could happen with the ESRA—that some important parts of the transformations we are seeking could happen as we build more support for the amendment.

Experience has taught us that many more people pay attention to a proposal when it addresses changing power relations in the society and using the mechanisms already in place to accomplish that goal than they do when people are advocating something that has no such mechanism available. The amendment process is extremely difficult, but it is not impossible, and people can see that; that makes it far more likely to be given attention, particularly if local city councils start to endorse it, and along with them some local and national elected officials, policy experts, and public celebrities in media, sports, or intellectual life.

Not at all. If such an amendment emerges, we will support it also and take both amendments seriously when we approach elected officials or others. We will explain why we have two amendments, and we will be happy when we get the opportunity to use such amendments to explain the picture of eroding democracy and environmental crisis and why we need both amendments to help repair American society and the planet.

As long as elites of wealth and power exercise effective control over the media and elections, the Congress and the president, regardless of their political party, will have to spend much of their time appealing for funds from those elites. There is no chance that they will then be willing to implement an amendment that seriously and permanently undermines the power of those elites. Most Americans intuitively understand that, and this is part of the reason they have considerable skepticism or even cynicism about the electoral process. To imagine us passing an ESRA that is just a few general principles and gives wide latitude to the Congress to implement them (as previous amendments were able to do) would seem pointless to most Americans. It becomes a serious endeavor only if we spell out in some detail how this might work—something that makes enough sense on the face of it to excite people to the point where they’d be willing to say, “Yes, this is a vision I am willing to struggle to obtain.” Similarly, without this level of detail, a Supreme Court could reinterpret whatever the people passed in a way that would satisfy the elites of wealth and power.

America was founded on the belief that there needed to be constraints on the power of the powerful, and that idea was incorporated into our Constitution, with regard to political power. Now we are taking the same step in regard to economic power. The best way to do that is to give that power back to ordinary citizens.

And yes, it will be scary to many people, which is why we need to be patient and persistent in the coming years and continue to put this idea forward, over and over again, because eventually more and more people will come to agree that it is the minimum change needed to save the planet and to save democracy. Gentle but firm persistence is needed—not simply one big push after which, if we don’t win, we all go home in despair! If passed, these would be some of the most significant changes to our Constitution since the Fourteenth Amendment empowered Black people in the United States, so we won’t be surprised about the resistance. And while supporting this, we can continue to do other political work as well, as long as we keep this in the forefront of our activity. Many liberals and progressives focus much of their attention on what they are against. The ESRA is an important balancing element, putting forward a coherent view of what we are for, particularly when conjoined with the Network of Spiritual Progressives’ campaign for a Global Marshall Plan to eliminate global poverty, homelessness, hunger, inadequate education, and inadequate health care, and to repair the environmental damage done to the earth. The Global Marshall Plan, however, is unlikely to pass Congress unless the elites of wealth and power are constrained by the ESRA.

There are many important things we can do to help the environment as individuals and as consumers. The ESRA mandates strengthening that kind of activity by teaching environmental responsibility at every stage of the public education process.

Yet we also have to acknowledge, after forty years of relying primarily on that strategy, that the world is in considerably worse shape because corporations in their frenetic pursuit of profits have frequently degraded the environment in order to increase their profit margins. The damage done to the earth by British Petroleum’s Gulf offshore drilling was possible because the Obama administration issued the company a permit to dig a mile into the earth, offshore. The destruction of our waterways, our air, and our land cannot be prevented by buying products from nonpolluting firms, because it only takes a small amount of corporations pouring poisons into the environment to destroy the planet, and this they will continue to do as long as they can make profits from doing so.

The ESRA will stop all that.

Deceptive campaign strategies often move the focus of a campaign away from major issues and solely toward the personalities of the candidates. By requiring equal exposure of both candidates and issues, the ESRA will get issues back into the forefront of campaigns. “Equal” means that no candidate will be able to have greater exposure than any other by virtue of having more money at her or his disposal. Similarly, by requiring equal time to be given at a specified minimum amount, free, to candidates in the last three months of an election, while prohibiting candidates from using money to buy their own time (the usual way that the cost of campaigns gets wildly escalated), the ESRA seeks to reduce the costs of getting candidates’ messages to the American people. The requirement of free time is the minimum level of social responsibility required of media, which use public airwaves and streets to get their messages out. It does not in any way impinge on the free speech of media except to the extent that it requires the media to give equal time to others (and if that is deemed to be amending the First Amendment, it is a good amendment for it to have, since freedom of the press has come to mean freedom for those with the money to buy and control media and indoctrinate the public with their perspectives, not allowing other perspectives to be heard).

For several decades after World War II, the Federal Communications Commission maintained a “fairness doctrine” that required media corporations to give “equal time” to alternative views—to those who were being critiqued or marginalized in the media. Toward the end of the Reagan administration, that requirement was lifted, so that media corporations no longer have any obligation to provide a balanced perspective—and hence supposedly are “freer” to present the news in any distorted way they choose. We want to make freedom of the press real, and that means allowing a range of views to be heard. Of course, this freedom comes with a cost—people will be exposed to views very different from those supported by the sponsors of the ESRA, but that comes with the turf of creating a more democratic society. It is our view that when given equal access to ethically grounded visions of the future, Americans will, over time, be won to a vision that demonstrates concern for the environment, social justice, and peace. Those who fear the American public will, of course, not be happy with the ways that we are extending democratic rights and making them more real.

No serious campaign to save the environment from global catastrophe in the twenty-first century can work unless the moneyed interests that profit from environmental irresponsibility are limited in the impact they have in choosing our elected officials, and the way to do that is to free the elected officials from having to spend an inordinate amount of their time raising money from the wealthy.

This statement accomplishes several things at once. It creates a responsibility that must be fulfilled by the president, Congress, the states, and the judiciary—thus extending the power of ordinary citizens to hold these parts of our government responsible. It requires that that responsibility be not just for the United States, but for the well-being of all who live on the planet, thereby creating a new urgency for something like the Global Marshall Plan or at least the One Campaign and the UN’s millennium goals. It provides the foundation for legislation to prevent the militarization of space or use space as a dump for all the irresponsible waste we produce on Earth. And it ties our well-being to the well-being of everyone else on the planet, a conceptual jump necessary for anyone to survive in the twenty-first century and beyond. The preamble and broad statements of this sort help to establish for future courts the underlying intent of those who support the amendment, making it harder for future Supreme Courts to attribute to the amendment meanings that are the opposite of what we intended.

Attempts to regulate the corporate influence in government, industry and media have proven inadequate, in part because every regulatory body gets filled up with people who share the fundamental assumptions of the industries that they are supposed to be regulating. While there is no absolute guarantee that the ideologies of the dominant society (with its strong emphasis on individualism, materialism, competitiveness, and accumulation of wealth at all costs, as well as its fantasy that even those who are beaten down might benefit someday from the same wealth that they do not hold today) won’t also influence many of those in a randomly selected jury, there is at least a reasonable chance that such a jury will have among its members those who have alternative views and who will listen impartially to the testimony of those whose lives have been impacted by the operations of the corporation being assessed.

Most major cities today maintain “civil grand juries” that perform a function similar to the one we are proposing: civil bodies, outside the control of the powerful, that help assure democratic control over major concerns affecting our society. Our existing jury system in criminal justice is among our nation’s greatest contributions to unbiased decision making affecting people’s liberty and basic rights (which is one reason the powerful keep trying to pass legislation or get their conservative-dominated courts to restrict this system and keep personal liability trials out of the hands of these juries).

We trust juries with our own lives: we give them the ability to decide to indict us for a crime, to decide our guilt, and to decide in capital cases whether we should be allowed to live or not. Corporations are not natural entities but legal constructs. They do not have the same claim that human beings do for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, or for being treated as sacred or created in the image of God. So if we trust human life to a jury, we can certainly allow corporate life to be determined by a jury.

As to unpredictability, all of us face this problem when faced with a government that may wrongfully charge us with cheating on income tax, speeding in a car, or even more serious offenses such as theft or murder. People who are familiar with the workings of our criminal justice system knows how important it is for each side to get a judge who will favor their kind of approach, and they will also do what they can to get jurors most likely to support their side of the relevant issues. So, yes, unpredictability is built into democratic procedures. On the other hand, the unpredictability of corporate decision making impacts on the entire human race and on the survival of the planet, so what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. We know that corporations will always seek to maximize money, but that leaves so much unpredictability in our lives that we hardly have a clue how the world will look in twenty more years of unrestrained corporate power.

On the other hand, the ESRA mandates that a jury give special attention to at least eight issues that it spells out in considerable detail in Article Two.

We are not trying to set up a system to govern every mom-and-pop operation or even relatively significant corporations that do not make large profits. They will be impacted, nevertheless, by clause eight, which holds that government contracts will be given to corporations that can, while proving they can carry out the terms of the contract at a reasonable price, demonstrate a satisfactory history of environmental and social responsibility. The desire for such contracts will have an impact throughout the economy and extend the benefits of the ESRA to many corners that will not be at risk of losing their corporate charters like the super-large corporations will, but may nevertheless face competitive disadvantage by failing to be environmentally and socially responsible.

The first sentence of Article Two makes it clear that social and environmental responsibility toward others and the planet is an obligation of everyone, even though only very large corporations are subject to the re-chartering and jury review requirements. It states: every citizen of the United States and every organization chartered by the United States or any of its several states shall have a responsibility to promote the ethical, environmental, and social well-being of all life on the planet Earth and on any other planet or in space with which humans come into contact.

Not at all. We recognize that there are many, many people in the corporate world who are fully ethical and ecologically sensitive. Many of them feel bad about decisions made by the corporations for which they work. They may go home and in their personal lives join environmental organizations like the Sierra Club or Greenpeace or the Natural Resources Defense Council. But at work they feel powerless to change anything, for one very important reason: the laws and Supreme Court decisions of the United States require corporations to do their best to maximize profits, and corporate leaders can be sued for failing to make a good faith effort to do so! So people working in the corporations quickly learn that they cannot put the needs of saving the planet above the need to make profits for the corporations.

When the ESRA comes into the picture, the hands of these many environmentally sensitive corporate leaders get immensely strengthened. With the ESRA, they are now empowered to say to their boards of directors and to their stockholders: “In order to protect your investments, we had no choice but to take extraordinary measures to be environmentally and socially responsible so that we would have a strong record to show to a jury that might, without such a record, take away our corporate charter and put your investments at risk. So in order to maximize your profits from investing in our company, we had to make it more environmentally responsible.” In other words, with the ESRA in place, the many good people inside corporations will have a powerful legal ally on their side to make corporations more environmentally responsible.

A constitutional requirement for Congress and any educational institutions that receive public funds directly or indirectly to pay attention to and give serious priority to these issues can in fact be legislated, just as we were able to legislate equal rights for people of color and for women and LGBT people.

The central point here is that we cannot expect the people of our country to be able to rationally deal with the problems of the global environment unfolding in the twenty-first century without providing them with the relevant skills and supporting the values that will make global cooperation possible. Requiring schools to teach these new skills and values is essential to making it clear that the matter of preserving Earth is not just an issue of private opinion or subjective choice but rather expresses the democratic will and legal legitimacy of the people as a whole. In this respect, mandating environmental literacy is equal in importance to the decision to mandate students’ ability to read and write and learn basic arithmetic.

We are facing the possibility of the end of civilization and human life on this planet, and unless we take this challenge as the primary national emergency, we, our children, our grandchildren, and many nonhuman species will not survive. This requires a fundamental reorientation of our educational priorities. It may no longer be as important for “success” in the twenty-first century that students have mathematical skills above the level of advanced algebra or that they be able to memorize a set of facts as it is that they know how to care for each other’s health and emotional well-being and for the earth, and know how to grow food, build homes, create activities and produce goods that are safe rather than destructive to the planet, are committed to nonviolence and to cooperation with people around the globe, and learn how to be genuinely respectful of others with different religious, political, and cultural norms.

Many will find that impossible, because the United States can require the same terms for corporations that operate outside the United States but function inside the United States to sell their goods or to engage in commerce or sale of stock. Article Four makes this kind of escape very difficult, because it would require that any corporation seeking to move in this way would have to get permission from a jury that would be empowered to seize all of the assets of that corporation if its move significantly hurts the environment or the communities in which it has been operating.

That’s the beauty of a constitutional amendment: it controls the Supreme Court, not vice versa.

Yes. It suspends all of those agreements made by corporations that have concocted a set of agreements to limit our democracy and to impose trade regulations that would favor the rich over the poor. The ESRA revokes them to the extent that they are in violation of the terms of the ESRA. International agreement breaking has been the stock-in-trade of the political Right. Now it’s time for us to break economic arrangements written to advantage the corporations and disadvantage the planet Earth and most of its inhabitants.

The underlying worldview has been with us for thousands of years in the major religious and spiritual traditions of the human race. It is a worldview that challenges the notion that money and power are the most important aspects of life and that we should orient toward the world primarily from the standpoint of how much we can “get” from other human beings and from the planet to satisfy our own needs. Rather, it affirms the centrality of love and compassion—or what we in the NSP call “The Caring Society”—caring for each other, and caring for the earth.

We in the NSP have another way of labeling it: we call it the “New Bottom Line.” Instead of judging institutions or corporations or social practices or government policies or even our personal behavior to be “rational, productive, or efficient” primarily to the extent that they maximize money and power (the old bottom line), we insist that they also be judged efficient, rational, or productive to the extent that they maximize love, caring for each other, generosity, compassion, kindness, forgiveness, nonviolence, respect for difference, and ethical and ecological sensitivity, as well as enhance our capacities to treat others as embodiments of the sacred and to respond with thanksgiving, joy, awe, wonder, and radical amazement at the grandeur and mystery of the universe. If you can buy this New Bottom Line, then, whether or not you believe in God, from our standpoint you are a “spiritual progressive” and we encourage you to join us!

There are people who say that this is compatible with capitalism, and there are people who say it is not. We welcome both to support the ESRA. From our standpoint the key is this: not what you call the economic and social system, but the criteria you use when making decisions in the boardrooms of our corporations, in the halls of government, in the bureaucracies, in the community organizations and professional organizations and unions and political parties, and in our own personal lives. To the extent that the institution uses the criteria of the New Bottom Line, we don’t care what label you give to the social or economic system. And to the extent that the New Bottom Line is not, in the final analysis, what determines the outcome of your deliberations, it’s not the system we support. Call it what you will—we are not interested in nineteenth- and twentieth-century debates about capitalism, socialism, or communism. We are interested in building a society that is environmentally sustainable and filled with love and generosity, social justice and peace, and joy and celebration of all that is. We are interested in building institutions that preserve the earth for future generations.

Every significant change in American history has seemed completely “unrealistic” and outside the mainstream until people decided to struggle for it. Abolition, women’s suffrage, the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, the women’s movement, the movement for rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transsexuals—all were dismissed as totally unachievable in the first few decades that people fought for them. But today they are all seen as just the inevitable outcome of social processes. So it will be with the ESRA. However, there’s one difference: we don’t have time to let the corporations do more damage to the earth. At a maximum, we’ve got ten to twenty years before we may have to accept that human civilization is doomed. But we are not there yet, and so there is a certain urgency to take the minimal steps proposed in the ESRA.

Yes, politics is the art of the possible, but one never knows what is possible until one puts one’s energy, time, and money behind goals that are necessary for the well-being of the human race and the planet. It’s only in the course of those struggles that we learn how many things dismissed as impossible are actually possible because they correspond to the deepest need structure of the human race and of the planet.

No. We encourage NSP members to form coalitions around support for the ESRA and the Global Marshall Plan as long as we stick with those specific proposals. We encourage a wide variety of groups to endorse the ESRA and Global Marshall Plan and to become actively involved in any way that they see fit to build public support for those campaigns.

Well, it would help us immensely if you did join the NSP, which is the organization that developed the ESRA and the Global Marshall Plan (you can join the NSP and read about the Global Marshall Plan at spiritualprogressives.org).

Here are some additional steps you can take:

1. Talk to neighbors, friends, family, church groups, labor unions, professional organizations, and civic organizations and get them to officially endorse the ESRA or sign the statement online and/or donate to the NSP so that we can hire people to work on this campaign.

2. Create a local group of people backing the ESRA and meet with locally elected city council members to get your city council to endorse the ESRA. Then do the same with your state legislators and your congressional representative and U.S. senators. Each year, go back with more and more people whom you’ve convinced to support this effort.

3. Set up a monthly meeting to discuss articles in Tikkun‘s Web magazine and involve people in the worldview that is behind the ESRA.

4. Create a monthly celebration of all who are engaged in social change activities.

5. Go door-to-door and get people to discuss and then sign the ESRA.

6. Create a caucus of spiritual progressives in your local political party, whatever that might be, and focus on building support for the ESRA, the Global Marshall Plan, and the New Bottom Line in your political party.

7. Help us financially—organize fundraisers, approach people with money and help them understand why what we want is what is ultimately in their own best interests, and approach foundations and corporate organizations and seek to bring them on board as well.

8. Continually challenge the mainstream media and the mainstream politicians—and be as respectful as possible and/or as rowdy as possible, whatever works best with your own personality, so long as you keep it 100 percent nonviolent.

9. Help us create local conferences of spiritual progressives to give one another support and deepen one another’s understanding of the tasks that confront us. And create celebrations, holidays, picnics, outings to cultural events, and anything else that nourishes your soul and the souls of others you’ve managed to recruit to the NSP.

10. Take time to nourish your own soul and make sure that your political work for these tasks is done in a manner consistent with the goals we ultimately seek to achieve. We must be compassionate for each other’s failures and moments when we do not live up to our highest ideals, but we should always strive to make our movement more and more an embodiment of the love and generosity we seek to create in the larger society. Love and compassion for ourselves, each other, and the planet come first and must be central to the way we live our lives and the way we present ourselves to others.